This post is a collection of my notes from the Learning How to Learn course on Coursera.

The Human Brain

We know very little about our brains, despite years of research by neuroscientists. It is humbling to realise that we know more about the universe than our own brains. The brain is the most complex organ we have, and it consumes nearly 20% of our daily caloric intake.

It was widely believed that each person was born with a certain number of neurons that make up the brain matter. These neurons atrophy as we age, leading to cognitive decline in our later years. However, latest research indicate that new neurons continue to develop in certain areas of the brain, such as the hippocampus. This neurogenesis is triggered by mental stimulation, and we can retain these neurons if we keep using them. So, in effect, we can keep our minds sharp by learning new things, and putting our brains to use.

Our brains use two types of signalling to work. There is electrical signalling that happens between neurons, which help us remember, and learn new things. And there is chemical signalling, which is slow, but perform some important functions. You might be familiar with some of these chemicals. There is Dopamine, which is essentially our rewards hormone. Dopamine motivates us to work towards our goals: short term, or long term. There is acetylcholine that helps with brain plasticity, which help us learn new things. And there is serotonin, or the stress hormone. It maintains our risk-taking behaviour, and is tied our social interactions. Higher serotonin levels are found in socially active persons, and low serotonin levels are associated with people with criminal behaviour.

The pre-frontal cortex is the area of the brain that is situated right behind our forehead. It is the region of the brain that that develops at last, and houses the leaning, planning, and language centres of the brain. This part of the brain guides our social interactions, gives us the ability for decision making, to plan ahead, and perform complex analysis. In short, it is our pre-frontal cortex that makes us humans.

Our emergence as the pre-eminent species on this planet is largely due to our superior brain. We have no problem remembering names of things, what they do, or how they work together. It is our ability to understand, and put together complex, abstract ideas and patterns that make us superior to other species on this planet.

Focused vs. Diffused mode

Our brain works in two distinct modes: Focused mode, and Diffused mode. The brain is in focused mode, when we try to solve a problem intensely. For instance, it is the state of mind we are in when we tackle a difficult math problem, or solve a complex puzzle. Imagine a torchlight casting a narrow beam on an object of interest. Under the focused beam of the torch light, we can see all the details of the object. This is similar to how the focused mode of our brain works.

The diffused mode is a little harder to explain. In this mode our mind is not actively engaged in a problem. Our mind casts a wider net, wandering among different ideas, and revisiting old thoughts. Going back to our torch light analogy, the diffused mode corresponds to a wider beam, that can illuminate a lot of objects at the same time. Although we can no longer see the details of a single object, we can identify many, and how they fit together in a big picture kind of way. For example, our mind is in diffused mode when you go out for a run, exercise, or when we are doing chores, such as, washing dishes.

To learn new ideas, we need help from both focus modes. The brain will alternate between these modes as it tries to grapple with the problem at hand. After spending considerable time working on a problem in focus mode, it is a good idea to take a break. Activities like going for a walk, exercising, etc. helps us get into diffused mode. In diffused mode, our brain revisits the old ideas even if we are not actively thinking about it. This is the reason, why we have those Aha! moments, at times. We tend to arrive at new ideas, or solution to a hard problem when we least expect it, during our downtime. Have you had a sudden idea while in the shower? That’s your diffused mode at work. History is full of such tales. Archimedes is believed to have come up with his famous Archimedes principle while taking a bath.

Chunking

The brain is a phenomenal organ, capable of many feats. However, to keep operating at peak performance, it has to be highly efficient. Our brain tends to group related activities together in what is called a ‘chunk’. If you perform, or revisit the same actions many times over, our brain becomes accustomed to it. We no longer need to pay full attention to each individual step to complete the task. For instance, backing out of the driveway in your car is a very difficult task at first, but with practice, it becomes second nature to us. Chunking might be an energy saving evolutionary adaptation.

A chunk refers to a set of neurons that fire together to perform some action.

In logical terms, a chunk is a set of action/idea with the same meaning. Imagine the word ‘POP.’ What does that conjure up? We may think of the individual letters, ‘P’, ‘O’, and ‘P’, or a pleasant pop sound. All these ideas are chunked together. In the neurological sense, a chunk refers to a set of neurons that fire together to perform an action.

The pre-frontal cortex houses our working memory. It is this region that we use when we are actively working on some task. It is believed that our working memory can host only about four chunks at a time. If we imagine these four chunks as slots, or pathways from where we can access the rest of the brain, we can understand why chunking is an important concept. With practice, chunks can become bigger, and longer, making it much easier to recall, and bring to your working memory.

How to chunk information

In order to form a chunk, we must follow these steps: concentrate intensely on the task at hand, understand the basic concepts of the idea, and understand its context. Let’s look at these in detail.

Focus: This goes with out saying, but learning new ideas are hard. So, don’t beat yourself up, when you are having a hard time learning a new concept. It is all the more important to concentrate on the task at hand with intense focus. This becomes much easier, if one can focus without distractions. This is the reason why we find it difficult to learn when we are in a noisy environment, or when we are constantly interrupted.

Understanding: Truly understanding a concept is very important. Without this, we won’t be able to efficiently chunk that idea. It is the understanding that cements the idea in our minds. Do not confuse this with Aha! moments. We may feel that we truly understood a concept after reading about it. But ask yourself this, will you still remember the key ideas after a couple of days? Do you know the concept well enough to explain it to someone else? If the answers to these questions are a resounding yes, then you have understood the concept.

Context: Context tells us why and where the concept fits in the grand scheme of things. Understanding the context help us see the top down, big picture stuff (where does this chunk fit). It also helps us see the bottom up view (what are the other chunks that are related to this one). Have you ever come across a new concept, and suddenly felt that it reminds you of concepts in another field? You have context to thank for that. This also means that chunks are sort of transferrable. This is the reason why the skills you acquire in certain fields are transferrable to others. This is the reson why earning to play the piano, or trying out martial arts may help you pickup other skills faster.

Procrastination

Most of us suffer from procrastination. We wait for the perfect time to start a project, waiting till we feel like it, often doing useless activities till we are too close to the deadline, and have no choice but to start the work. Why does this happen? When we look at procrastination as a habit, we can that they work the same way. Understand how a habit works, and we can break out of this cycle.

“You are not a procrastinator. You have a habit of procrastinating.” - Mel Robbins

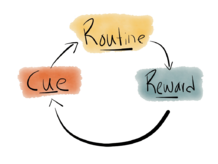

A habit works in four steps: Cue, Routine, Reward, and belief.

First, there is the cue that triggers the habit. This can be an external or internal stimulus. Examples for external stimuli are a place, the time of day, etc. Example for an internal cues is how you feel. The routine is some action on our part in response to the cue. Finally, the reward is what you get at the end of the routine.

Let take hunger as an example. When we feel hungry (an internal cue), we find food and eat (the routine), and we feel satiated afterwards (the reward). And the belief is what neatly ties all this together. Our belief that this habit works is why we repeat the same loop over and over again. You can read more about the habit loop in this Habitica article.

The Habit Loop. Image courtesy: Habitica.

Now how is this related to procrastination? Well, let’s look at a situation where we might procrastinate in terms of the habit loop. It’s time to study (cue), but you don’t feel like it, so you end up browsing the web instead (routine), and you feel relaxed when you do this (reward). We realise that if we change the routine from surfing the web to actually studying, we can break out of this loop.

When we are faced with new, and unfamiliar objectives, such as, leaning something new, our brain experiences unpleasantness in the pain centres of the brain. Literally this pain causes the brain to attempts to shift its attention to a more pleasant activity, such as, surfing the web. Once we start paying attention to the cues, it’s easier to realise this and change up our routine to avoid procrastination. Once we ignore the impulse to stop studying, and keep working, chances are we would keep on working.

Memory & Sleep

From what we have learned so far, we know that we have two kinds of memory: short term, or working memory, and the long-term memory. Our working memory is limited in capacity, where we can only hold about four chunks of information. This puts a fundamental limitation on how much information we can have in our working memory. We can view our working memory as a whiteboard, where there is a limited amount of space. To put more information on the whiteboard, we must make more room by clearing out old information. Our long-term memory, on the other hand, is more like a large warehouse. Although the storage capacity is large, we still need to access it through the four chunks in our working memory.

While learning new things, our goal then should be to move the ideas we have learned in to the long-term memory. In order for this to happen, the memory itself should be memorable. We can make something more memorable by associating it with other things that we already know. This is where analogies, and visualizing techniques help. These are effective techniques, as the brain is adept at retaining spatial, and visual information.

Practice makes permanent.

Another technique to help forming long-term memory is spaced repletion, and recalls. A memory is moved from the short-term memory to the long-term memory through a process called Consolidation. At this stage, the memory is weak, and would die away over time. When we recall this topic, the memory is brought back to our working memory, in a process is called as Reactivation. After working on the problem, the modified memory is then moved back to the long-term memory in a step that is called Reconsolidation. This is a cyclical process, and helps in forming stronger memories.

Importance of Sleep

Sleep is another factor that plays a major role in memory. Sleep is not just meant to provide us with respite from the struggles during the day. A lot of memory consolidation happens during the sleep. So, it is important that you get a good night’s sleep after a long study session. Waste from the neurons, and other impurities are flushed away from the brain during sleep. This is another good reason to have a good night sleep.

Learning strategies that does not work

While it is important to know what strategies help in learning, it is equally important to know what strategies does not work. These strategies give you an illusion of competence, and we need to be aware of them.

Overlearning

Have you ever read some material over, and over in the same study session, thinking that it would help you learn quickly? You are not alone. This is a strategy that is doomed to fail, as spending a lot time on a topic in the same session offers diminishing returns. You would be better off spreading your study time over multiple study sessions, coupled with sessions for recall.

Overlearning do have his uses, especially if you are planning to give a speech, or a presentation. In such cases, overlearning can be beneficial.

Einstellung

Einstellung is the German word for ‘mindset’. It refers to our predisposition

to solve a problem in a certain way, when better or more efficient methods

exist. Einstellung typically happens to us when we become experts in our

fields, and we look at other problems with that lens.

The strong chunks that are already formed in our brain on these topics prevent us from learning and forming new chunks. Our pre-existing biases, and prejudices interfere with adapting to the new field. Due to this, sometimes it would be necessary to unlearn old ideas before moving on to learn new ones.

Interleaving

Interleaving refers to working on different ideas during the same study session. This approach has a positive impact on learning outcomes. So, instead of focusing on just one topic, or problem, you would have better results by jumping back and forth between different problems sets, or topic in the same study session.

How to be a better learner

Now that we have covered strategies that does not work, let us look at learning strategies that do work.

Recall

Learning without recall is a recipe for disaster. Once you are done with a study session, close your eyes and try to recall what you have learned. The mental act of recalling the information help us with our understanding of the concept. Preparing mind maps of the topics after a study session is a good example for building your ability to recall.

Testing

It is important to test yourself after completing a couple of study sessions. To make this exercise more fruitful, practice past questions, and problem sets on your study topics. Testing has a twofold advantage: it helps you test how much you have really learned, and it takes the fear away from tests.

Spaced Repetition

We know that recall is an excellent tool to solidify your understanding. Spaced repetition can take it even further. In spaced repetition, we spread our recall and testing over time. For example, if you perform recall the next day after learning something, chances are you would remember it. However, if you test yourself a week later, how much would you remember? In such cases, recalling and relearning through spaced repetition would be a better strategy.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice is often confused with overlearning. In overlearning, one tends to practice on the easy parts over and over in a single session. This results in a false sense of competence. Deliberate practice works exactly the opposite way. During a deliberate practice session, one should focus on the parts that are hard, or parts they still have not mastered. This is a strategy that is employed by students of performing arts, such as, musicians, and dance performers, but we can adapt this strategy to others fields of study as well.

Pomodoro Technique

This is how the pomodoro technique works: you set a timer for a fixed length of time, and when it ends, you take a short break; this process is repeated 3-4 times, and then you take a longer break. When you hear the alarm going off (the cue), you sit down and work (the routine) till you reach your break time (the reward). The pomodoro technique leverages the habit loop mechanism to make us more productive.

Focus on Processes, not Products

When we focus on the end result -which is usually something big- such as, completing an essay by next week, we feel overwhelmed. Instead, if we focus on the process of writing a page per day for a week, the task suddenly feels more manageable. Thus, by shifting our attention from products to processes, we become far more productive.

Enlisting the help of Metaphors and Analogies

We can use our brains visual, and spatial powers to our advantage. Next time when you need to understand a new concept, try relating to the existing concepts you might already know. For example, let us say we are studying electricity. We can compare the flow of electricity to the flow of water. In that case, voltage can be thought of as similar to water pressure. Using such metaphors can help us relate complex abstract ideas in terms of tangible physical things. Another worthwhile strategy is to put yourself in the shoes of the concept you are try to learn.

Study Groups

If you have access to a study group, use it to further your learning and understanding. Study groups have many advantages. You can test your understanding of concepts by explaining it to others. Questions from group members helps you understand the gaps in your own understanding. However, these advantages can quickly be overshadowed if the group members do not meet regularly, or if they spend most of the time in idle chatter.

Final thoughts

I completed the Learning How to Learn course in 4 weeks, and I must say it was well worth it. It is taught by Dr. Barbara Oakley, and Dr Terrene Sejnowski, who are terrific instructors. The course is available for free ($49 if you want a certificate) on Coursera. If you found this blog post useful, I strongly recommend you to take the course on Coursera. Happy Learning!